These days, authors are expected to do most of their own promotion when a book comes out, especially if they are publishing with small presses. We design our own swag, set up our own interviews, and toot our own horns. For a group of people who tend towards introversion and self-criticism, this can be excruciating.

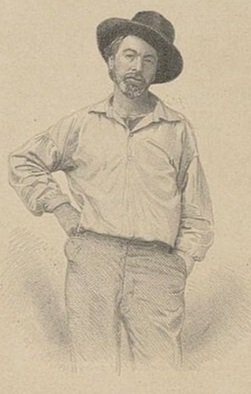

Some authors, however, take to self promotion quite naturally. Take Walt Whitman, for example. When he published the first edition of Leaves of Grass in 1855, no one knew who this peculiar Brooklyn poet was, and Whitman was keen to correct that problem. Oddly enough, Whitman didn’t put his name on the cover of the book (or on the title page), but the frontispiece did feature a nearly full-body portrait of the poet.

The portrait makes a statement. Whitman is dressed as a laborer, not a scholar. He wears no jacket or tie. He stands akimbo—his left hand sunk in his pocket, his right is propped on his hip. This is how he chose to sign his work—not as a name but as an entity, a full-fleshed person who needs to be engaged as such.

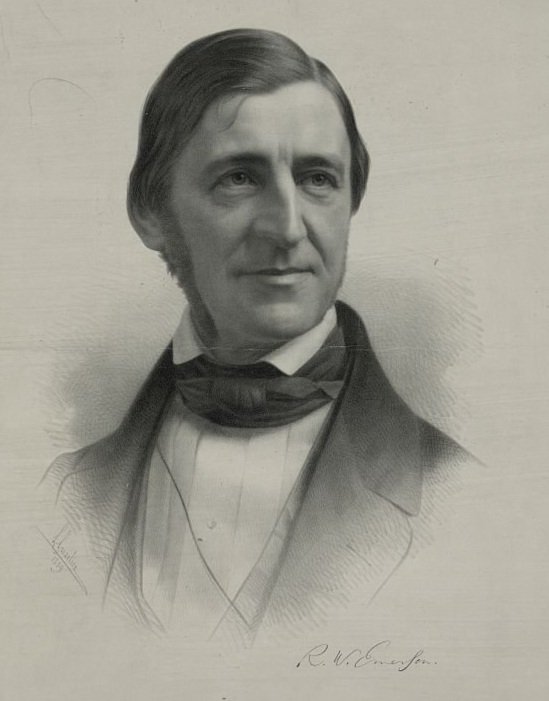

When the book was published, Whitman sent copies out to writers whom he admired, including Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson’s 1844 essay “The Poet,” which called for a national poet who could unite the good and the bad of the entire country in his writing, felt like a personal call to action for Walt Whitman. Leaves of Grass was his answer.

And Emerson loved it. He wrote as much to Whitman in glowing terms.

Dear Sir,

I am not blind to the worth of the wonderful gift of “Leaves of Grass.” I find it the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed. […] I give you joy of your free and brave thought. I have great joy in it. […] I greet you at the beginning of a great career, which yet must have had a long foreground somewhere for such a start. I rubbed my eyes a little to see if this sunbeam were no illusion; but the solid sense of the book is a sober certainty.

Let’s pause for a moment to appreciate what an incredible thing it must have been for Whitman to receive this letter from his idol. These are unqualified words of praise. There are no underhanded compliments, no condescending pats on the head. It’s pure and effusive appreciation from one writer to another. And it was everything Whitman had hoped for.

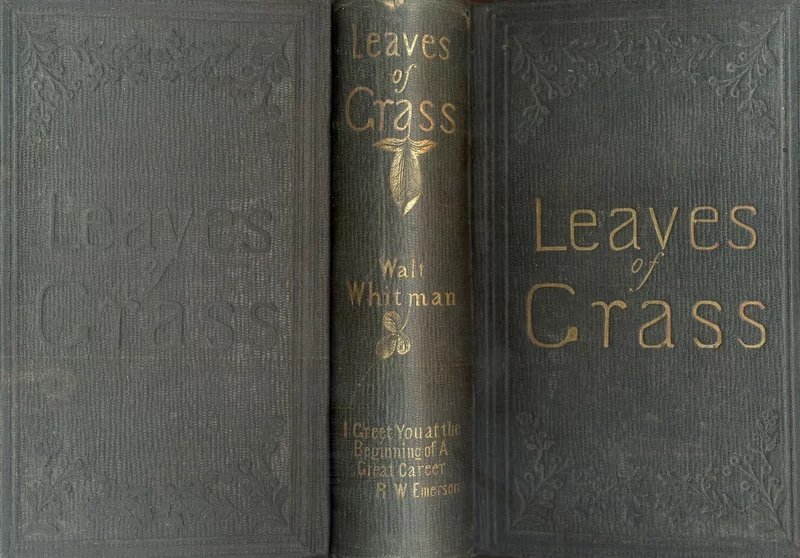

Whitman was so proud of this letter that not only did he reprint the thing in the New York Tribune, he pasted copies of it into the front of numerous first edition copies of Leaves of Grass, and—when the second edition came out—he embossed Emerson’s phrase “I greet you at the beginning of a great career” in gold letters on the spine.

Here, we ought to stop and chastise Walt Whitman, because he did these things without asking permission. There are conflicting reports as to whether Emerson himself was outraged about Whitman’s brazenness or whether it was his friends who held the grudge on his behalf, but the principle stands: you can’t do that. People have a right to expect that the things they say to you privately will not be published far and wide just because they are flattering to you. You have to ask.

And that’s the moral of this story. We, as authors, have to ask. Nothing is ours by rights. We have to ask people to read what we write. We have to ask our readers to tell their friends about our writing. We have to ask our mentors to say nice things about us that we can publish on our book’s cover. But this isn’t a bad thing. It means that we don’t actually have to do our self-promotion alone. There are plenty of people who will be delighted to help us usher our writing out into the world. They just need to be asked.

Not that every single person you ask will say yes. Some people are grumpy. Some people have said yes so many times that they need a break. But someone out there will be ready to help just as soon they know what you need.

Does it really work? Check out the blurbs for Millions of Suns on our book page.

Whitman was so impatient with this process, however, that he ended up writing several celebratory reviews of Leaves of Grass himself, which he also published, anonymously, at the end of the second edition—along with Emerson’s full letter. Not only is this not a good look (we’re still judging Whitman for it nearly 170 years later), it shortchanges the process of building a real community for ourselves as writers.

If you are struggling with the burden of self-promotion (I know I am), I encourage you to be like Walt Whitman. Identify the people who have influenced you, whom you admire, and whose opinion you crave. Let them know if your writing is an answer to a question they asked. Tell them what they mean to you. Invite them into a genuine relationship with you. Be more than a name on the title page. Be a full-fleshed, living person behind your book.

And also, don’t be like Walt Whitman. You aren’t the one and only Poet (or Essayist or Novelist or Memoirist), here to save the world. You are one among a multitude. And the more there are of us, the better. Your community will embrace you if you ask. They will lift you up.

But you have to ask.

This blog post was first published at https://www.bennerdixon.com/blog/self-promo